There are two very terrifying plush dolls.

Is that what a labubu is? It’s hideous, and not in a charming way

Two labibi.

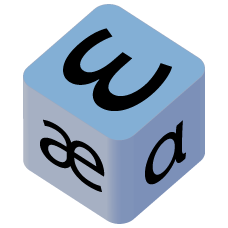

Foot -> feet

Book -> beek

Labubu -> labibiEasy.

shoop>sheep

Wouldn’t it be labubi?

Technically though it is permissible to modify other morphemes to aid pronunciation… or avoid childish names for body parts.

Interesting, a combination of native Germanic ablaut and loaned inflection!

Yup. Totally and exactly my intention… those things you said.

foot -> feet is ablaut, changing the vowel in the root, also in break-broke, etc.

-i is a non-native plural suffix, e.g. cactus-cacti, octopus-octopi (from Latin), it’s very unusual to loan these purely grammatical elements (morphemes)

Alternatively, labubu-labibi is a case of a changed transfix (singular: u_u, plural: i_i), or of vowel harmony. Either way, all very exotic for English standards :D

TY. Your first reply made me it and look up those terms!

This is exactly why I subscribed here today.

I’ve always wondered how non-native suffices come to be- do you know? To take the example, octopus is almost exactly the Greek original word. It’s understandable that octopodoi isn’t intuitive in English. But why not stick with octopuses, or the Greek/English-mix octopodes (I know both of them are a thing, too). How did a third language come into it?

It’s because -us is the Latin second declension nominative singular, and its nominative plural is -i. People educated enough to know the -us/-i pattern (cactus/cacti, alumnus/alumni, stimulus/stimuli) but unaware that “octopus” is Greek and has an irregular stem are likely to misapply the Latin pattern.

I thought as much, but was never sure. Could’ve developed more naturally, like from Romans in Britain, for all I knew.

In the case of English, it’s because of the knowledge of and prestige of Greek (and Latin). The higher more educated classes, who were traditionally taught classical languages, preferred to stick to the original declension, and they could spread this preference through grammars, dictionaries and schooling - but only to a certain degree. So it’s a somewhat artificial phenomenon, and it tends to have only a limited spread outside of those who were taught Latin and Greek (so people do spontaneously say octopuses, and sometimes they try to make a classical plural that is nonetheless “wrong”: octopi).

Similar stuff happens in some other European languages, I could list a few examples from my native Croatian where Latin grammar is supposed to be used, according to the wishes of some classical philologists, even when it clashes with all rules of native grammar (and, as expected, the latinate grammar is not used by anyone outside of a handful of academics).

At worst, such usage could be interpreted as social signalling of superiority (class + education). Obviously, nobody expects people to use “original purals” in cases such as gulag-gulagi, or wunderkind-wunderkinder, because Russian and German aren’t all that sexy, even though German is much closer to English than Latin or Greek are.

But there are more natural cases of loaning inflectional morphemes, in communities with a very high degree of bilingualism. I’ll admit I could only copy-paste some passages from books regarding this, I don’t have much knowledge of languages outside of Slavic and English.

This was so interesting to read, thank you! It felt like a mishap that just stuck rather than a natural development, but I never knew for sure!

Las bubu. Like those monsters who insist on “attorneys general”.

- mothers-in-law

- passers-by

- governors general

- notaries public

- sergeants major

- editors-in-chief

It follows a rule about compound nouns that is taught quickly around the 7th grade.

It follows French, where the adjective comes after the noun.

I don’t really understand the connection, since French has plural adjectives and English doesn’t. And in my head, that was also why the above list is the way it is- English doesn’t have plural adjectives, so of course you denote the plural through the noun. If it were French, it would be more like attornies generals. Not to mention that some adjectives go before the noun in French, and for those, it’s still both the adjective and the noun being made plural at the same time. I’m not a linguist, and also neither native in English nor French, can you explain?

Lots of modern English words came from French, especially Norman French.

These modern English phrases that follow this “noun then adjective” are French loan phrases (I think). Or, they were constructed to look like French loans, because French was the language of the nobility, a “higher” way of speaking than dirty, peasant English.

I thought the overwhelming majority of English words have Latin roots? That’s what I was always taught in Latin classes

Well … yes, but a lot of them went Latin > French > English.

I still don’t really understand how that pertains to why the plural -s goes with the noun in fixed phrases like attorney general

Because English doesn’t pluralize adjectives. English is a mutt of a language, and it doesn’t always make sense.

Yeah, that’s what I’m saying. That’s just what English does, and I don’t see what it has to do with french.

Or alternatively, due to turning the singular Spanish article “la” into the plural “las”.

For the uninitiated

Always two there are, no more, no less. A master and an apprentice.

It would be Labubukuna if you didn’t specify it, but since you did I guess it’s just two labubu.

Wtf, they made a gay language??

there are two labubi

It sounds sumerian so I think labubuene maybe?

Probably “labubu”. The -(e)ne suffix is mostly used with animated nouns, and since they’re toys I’m guessing people would use the inanimate with them instead.

…unless it’s part of some odd construction like “kings of labubu” (lugal labubu-k-ene) or “shepherds of labubus” (sipad labubu-k-ene) . Then you get the plural mark, but that’s because of “kings” (lugal-ene) and “shepherds” (sipad-ene); those Sumerian case/number marks behave more like clitics than suffixes.

You can also stack them, and it gets messy (like, “labubu-k-ak-a-ne” tier).

Like sheep. Two Labubu.

WTF is it with humans and plastic dolls of inexplicable attraction very decade or so?

one menu -> two menus.

one labubu -> two labubus.

One moose -> two moose.

One labubu -> two labubu.

Yeah, but moose is regular. Goose is irregular.

One goose -> two geese.

If irregular, we could have One labubu -> two lababa.

How many Joe are there over there?

Lebubai

One labubu, two ლაბუბუები (labubuebi)